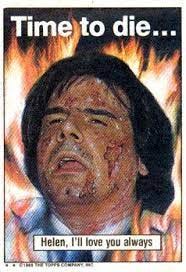

Time to Die

The unsubtle art of killing stories before they make it into the world

Very quickly before the article here. I am never going to charge for my Substack. I don’t write enough to justify that, and a lot of the writing I do in here is just selfish naval gazing anyway. But I am, at the moment, not employed full-time and so if you like these occasional missives and feel like contributing, that would be awesome. If not, that’s fine. Thanks.

A couple days ago I started my Substack chat, which allows me to interact more directly with readers (go check it out, it’s free and I say hi in there and you all seem very nice). The first thing I did with chat was ask “what would you like me to write about?” which generated a lot of really great ideas. Among the questions I got is one that was either deleted by its author or was cooked up by me in a fever dream. As an aside, it would be very funny if I asked you for topic suggestions and then just wrote an article based on what I imagined you to have written, but I am pretty sure this on existed [correction! - reader Kimberly noted it was in fact a suggestion from twitter user @candy_schopp]. Anyhow, the question was:

The other day you tweeted about stories you liked, but had to kill, would be really interesting to read what some of the thought process is to decisions like that for a working journalist

It is a good question and not an easy one to answer because it gets into not only the nuts and bolts of writing stories about other people, but to the very core of the ethical conundrums contained therein. But I hope I can write something that is interesting and/or instructive about this. We’ll see!

So just for context, the reason I tweeted about killing stories was because Bari Weiss used her website to publish the second in a series of articles about how transgender healthcare in this country is predatory and targets kids. In this particular story (which I will not drive traffic to, because fuck that), a mother laments to writer Emily Yoffe that her child was given a puberty blocker to address their gender dysphoria. However, almost as soon as the story was published, the child at the center of it posted refutations of many of the salient parts of the story on twitter, said that they were shown a draft of the story in advance (more on that later) and had many of their concerns ignored. In response, I tweeted the following:

I - God damn, where to begin with all of this.

I guess the first place to start is with what I think journalism should be. In its purest form, journalism should be a collection of information that informs the way the reader sees the world. The notion that it shouldn’t have a worldview or an editorial standpoint is ridiculous, and a fiction that is often used to impugn good journalism and good journalists.

In fact, there’s too much of that going around. There is nothing that frustrates me more than reporting that goes something like “on the one hand, there are people who are trying to destroy peoples’ civil liberties, but on the other hand, those people don’t enjoy the destruction of their civil liberties!” It’s not just OK to form a conclusion based on a fact pattern, it’s important. It helps people create meaning from the thing they have just read or watched or listened to. I’m sure my conclusion is not going to be that of everyone who experiences the thing I’ve made, but think back to literally any Reply All story, and imagine that it had no trace of my opinions or conclusions in it. It would be a bad story where no one learns anything and it has no contour or depth.

A very important caveat to that is that I need to pursue a story knowing that I come to it with my own biases. I need to constantly be aware of them and challenge them by asking the right questions. Because if you don’t do that, you are going to look for information that fits a narrative you already believe. Don’t get me wrong - I think skepticism is great and a superpower, and I wish more journalists had it in the face of press releases from governments and police departments and tech companies. But to actually make something you can be proud of, you also sometimes have to skeptical of your skepticism, if that makes sense. Knowing that you’re entering a story with a point of view means you have to challenge it in the reporting process.

Take for example “Long Distance,” the story I’m probably best known for. If you haven’t heard it, it starts with me getting a call from a phone scammer, and balloons into a story about the call center in New Delhi from which the call originates. I think that everyone hates scammers and the work they do, but if I had just left it at “I hate scammers, I’m going to mess with them,” I wouldn’t have gotten to what I think is the meat of the story: that the people in those call centers are themselves often exploited and underpaid, and in certain cases, intimidated and harassed and occasionally assaulted by their employers. In interviews with the people who had worked there in the past, we were told that they were lied to during the hiring process, often had their paychecks withheld for months, and were intimidated sometimes into working well past the shift’s end in order to reach sales quotas. They told me they had seen employees attacked by their supervisors. Sure, they called me and annoyed me, but they were victims of circumstance and some dismal economic prospects.

Life is messy and complex and my experience of it is messy and complex too. If I am going to contribute something to the world that helps people understand it better, I need to be able to interrogate my own experiences in the process of writing about other people. That’s why I find journalism from anecdote (“I’ve never experienced this, therefore it must not be real”) to be so infuriating, and so easy to check.

II - OK, so what does this have to do with killing stories

I wrote all of that preamble because according to the subject of the Emily Yoffe story, their refutations of the Yoffe’s narratives were ignored, and the story the mother told was framed as fact. They also said that they did not want the story to come out and made that very clear. Now, as a journalist, you are going to have to write stories where there isn’t cooperation from the main character and where the main character definitely doesn’t want it to come out. Elon Musk is going to send me a poop emoji if I ever ask him for an interview, but I still think he’s worth writing about. But when producing journalism, you need to have a sense of the relative power of the subject of the story. Musk is a billionaire, the owner of several companies, a very public figure that has a habit of making his opinion known. Writing about him is writing about a person who wields power greater than the author, and greater than most of the readers. However, the more vulnerable a character in a story is, the more you have to balance the newsworthiness of the story against the poetenial to harm the subject. I’ll use three examples from my experiences at Reply All to illustrate.

I was working on a story for a while about a person who experienced a lot of online hate that was also the subject of some websites that posted information about celebrities and their net worth, among other things. This person, who is a public figure but to call them a celebrity is a bit of a stretch said to me “hey, can you look into this and get them to take down this information, because its not correct, and the untrue net worth info is just another attack vector for these people to harass me.” The value of telling their story was as a humanizing framing device for where these celeb net worth sites come from and where they get their information (turns out they mostly get them from one another). However, the person at the center of this harassment was so traumatized that I eventually felt like doing the story would revictimize them, and I really couldn’t justify using them as a framing device just to give people another avenue for attack.

A relatively young guy approached us about a situation where a very powerful company threatened him with a lawsuit for leaking information online. Their threats and intimidation tactics were (in my opinion) not at all commensurate with the perceived transgression against the company. He reached out because he was angry at the way he was treated by them and was genuinely worried he was going to get sued. Before we got to the end of the reporting process, we reached out to a lawyer and the lawyer said “yeah, they probably aren’t going to sue you. It’s almost certainly just a threat. That said, they’re not going to love you doing a radio story about it.” At that point the subject said he no longer wanted to move forward with the story. Now, he had agreed to talk to us on the record, had provided us with information about the company that threatened him. We had a few hours of interview with him and a ton of detail. But without his cooperation, what do we get out of it? We become as predatory as the company themselves. The details of the story are great, but it’s not a shock that powerful corporations victimize individuals, and if the main character here is not interested in putting up a fight, I’m certainly not going to poke a hornet’s nest that might provoke a lawsuit. The journalistic standard is that if someone speaks to you on the record and changes their mind, then it's your discretion whether you finish it or not, but it’s one thing for a politician or some bad actor to pull that, an another entirely for some private citizen that has agreed to talk to you but may face significant consequences for doing so.

A story that actually ended up airing, Who’s Going?, aired in a markedly different form than it began. The story was about a teenager named Adrian who had posted his birthday party invite online. That invitation ricocheted around Tik-Tok and went from a couple kids who were planning to hang out on the beach to a completely insane two-day quasi-riot on a beach in Southern California. Initially, we wanted to tell a story about Adrian himself. he was turning 17, wanted to have some fun with his friends, suddenly became the subject of an intoxicating level of attention, and then the whole thing got away from him. However, when we reached out to Adrian’s family, they declined to talk to us. And that changed the calculus of the story entirely.

Interviewing minors, or making them the subject of a story, is delicate. Each news organization has its own standards, but Reply All made sure the parents of minors in our stories consented to their participation, and when we couldn’t confirm that Adrian’s parents had consented to audio/video recordings given to other news orgs, we had to reevaluate. We basically said “ok, we don’t have the cooperation of Adrian or his family. We don’t know if his parents consented to him being recorded. This story still fascinates us. How can we tell it?” In the end, we removed the audio we didn’t know his parents consented to from the story. We actually shifted the story away from Adrian entirely. We decided instead to get the perspectives of a bunch of people who had been there. It was an attempt to make a kind of sound rich, Dazed and Confused version of the story. And honestly, I’m not sure it worked! It was hard to make and we had to tear up a draft and start mostly from scratch pretty late in the process! But I think we made the right decision in regards to shifting the focus away from Adrian. And, you know, they can’t all be winners.

Those are three concrete examples I can remember killing. There are dozens more I’ve forgotten because they played out something like this:

I have a hypothesis about the way the internet or system or a company works.

I go talk to primary sources for the story and they say either “yeah you’re kind of right, but the truth of it is actually way more mundane than you think and there’s not much to learn here” or “actually, you’re completely wrong about this. Here’s the long boring truth.”

I go to my senior producer and say “Hey, that story is dead, because I was wrong about hot that works.”

It’s OK to believe something and be wrong. In fact the function of good journalism is to correct things you’re wrong about. I have, on more than one occasion, built the opinions I was later disabused of into the story I am working on. The problem begins when you have a notion that you believe so strongly that you refuse to consider any information that counters it. According to the subject of the Yoffe story, that’s exactly what happened. In fact, according to the subject, Yoffe sent them a draft of the story prior to its publication. That caused a lot of journalists to throw up their hands in surprise and disgust, because that’s a big journalistic redline, and I wanted to try and explain why that’s the case.

As I mentioned earlier, in my opinion the job of a journalist is to establish a pattern of facts and then synthesize that information into something coherent. It is our job to create meaning from noise (which, I’ll say again, requires having an opinion). On Reply All, we had a fact checker who would go through our stories (even Yes Yes Nos) with a fine-toothed comb and email the subjects contained therein to make sure that we weren’t misquoting or robbing them of context. But sending an entire story opens you up to being manipulated by sources or subjects. They could argue with your narrative or threaten you with legal to try and keep information out of the story. I mean, that’s what PR people do already without getting the whole story. Independent of that, it looks really bad if it comes out that you gave a draft to one source and not another. It looks like favortism and will open you up to charges of bias. And it’s especially bad if, as is being claimed in the Yoffe story, you share a draft, the subject says it’s incorrect, and you publish it anyway.

III - Ok so what

I don’t know, man. There are a million stories I’ve had to kill for some reason or another that I will forever hold out hope will one day be viable again. Reply All had a folder on our server called “The Graveyard,” where all the interviews and half finished stories went. There was always a vain hope that one day one a source would appear or we’d get an email that would let us unearth those buried stories. But when I’m working on something, my obligation is not just to tell be engaging, but to do right by both the audience and the subjects. And sometimes that means killing a story you think will be interesting or illuminating, knowing that you will be doing a greater disservice to those involved if you continue to pursue it.

There are, of course, best practices when trying to tell a good non-fiction story. But there aren’t a series of if/then questions you can ask to tease out the ethical quandries of reporting. In the end, that is the responsibility of the reporters/editors/and fact checkers. And they don’t always get it right. I’ve screwed up in the past and I’ll do it again in the future. But in my opinion it’s better to kill a piece and wistfully imagine what it could have been than to let it out into the world and regret it forever.

A thing I liked this week

Lil Yachty put out a record that sounds kinda like Pink Floyd. It’s weird. Real fat synths.

Well, the title of this freaked me the fuck out.

This is a really interesting piece! Thank you, it's really cool to see behind the curtain 💙

I loved this - thank you. Cool to hear stories from the graveyard.